Starlight Distillery

By Meghan Swanson

THE CUT

Location: Starlight, IN

Capacity: ~4,000 barrels yearly

Still type: Pot, soon to be pot-column hybrid

Still manufacturer: Vendome Copper & Brass

Barrel size: 53 gallon

Cooperage(s): Independent Stave Co. (ISC), Kelvin Cooperage, Canton Cooperage, Seguin Moreau, Barrel Mill, Zak Cooperage, Radoux

Flagship Product: Carl T. Bourbon, Old Rickhouse Rye, and apple brandy

Year founded: 2001 (brandy distillation permit)/ 2013 (artisan distillation permit)

Farmer. The word conjures a whorl of images in the mind’s eye; at the center is probably a gray-whiskered man, face lined by decades of sun and wind and toil. A dying breed - his sons and daughters off making their way in the brave new world, the future of his life’s work nothing but a big question mark. Christian Huber, distiller and scion of Starlight, Indiana’s Huber Orchard and Winery, does not fit this image. Wearing a dress shirt and a pleasant expression, Christian speaks with infectious enthusiasm about Starlight Distillery, a comparatively new point gleaming in the Huber family’s constellation. He is far from the grizzled, overall-wearing archetype; at the time of our interview, he is coming up on his 27th birthday. Christian, his brother Blake, and their father Ted have married a farmer’s practicality with a scientist’s thirst for innovation and added the rich legacy of 7 generations of family knowledge and labor. The result is Starlight Distillery.

“We were never supposed to be this big. None of us were. Dad was happy making 200 barrels of bourbon a year, just being happy because it was with his sons.”

The Huber family’s distilling roots stretch across the sea, to Baden Baden, Germany. Simon Huber was the second son of a winemaking family - the ‘spare’, not the heir. As second sons were expectedto do in Europe, in the 1830s he struck out on his own to find his fortune. His feet led him to the New World, up the Ohio River Valley to the far southeastern tip of Indiana, and a place that would be called Starlight. The old-world vines Simon brought with him were devastated by Phylloxera, a microscopic pest and scourge of winemakers native to the eastern United States. He couldn’t make the wine he was used to, so he turned his skills to brandy made from hardy local brambles like blackberry and black raspberries. Like many American farmers, he also turned his spare apples into the popular spirit applejack. “It’s really unique to see how distillation wound its way through everything we had as a company, but not as the main focus of it. It was always for an added agricultural benefit. If we weren’t going to use or sell the apples in the fresh market … we were making it into apple brandy.” Christian points out.

Generations of Hubers continued to grow fruit, farm, and make their wine and fruit brandy up through the Great Depression. In the 1990s, Christian’s great-grandmother Marcella would talk his dad, Ted, into revamping the family’s distilling business.Christian’s grandfather, Gerald, and Gerald’s brother Carl, decided to venture into the winemaking business.

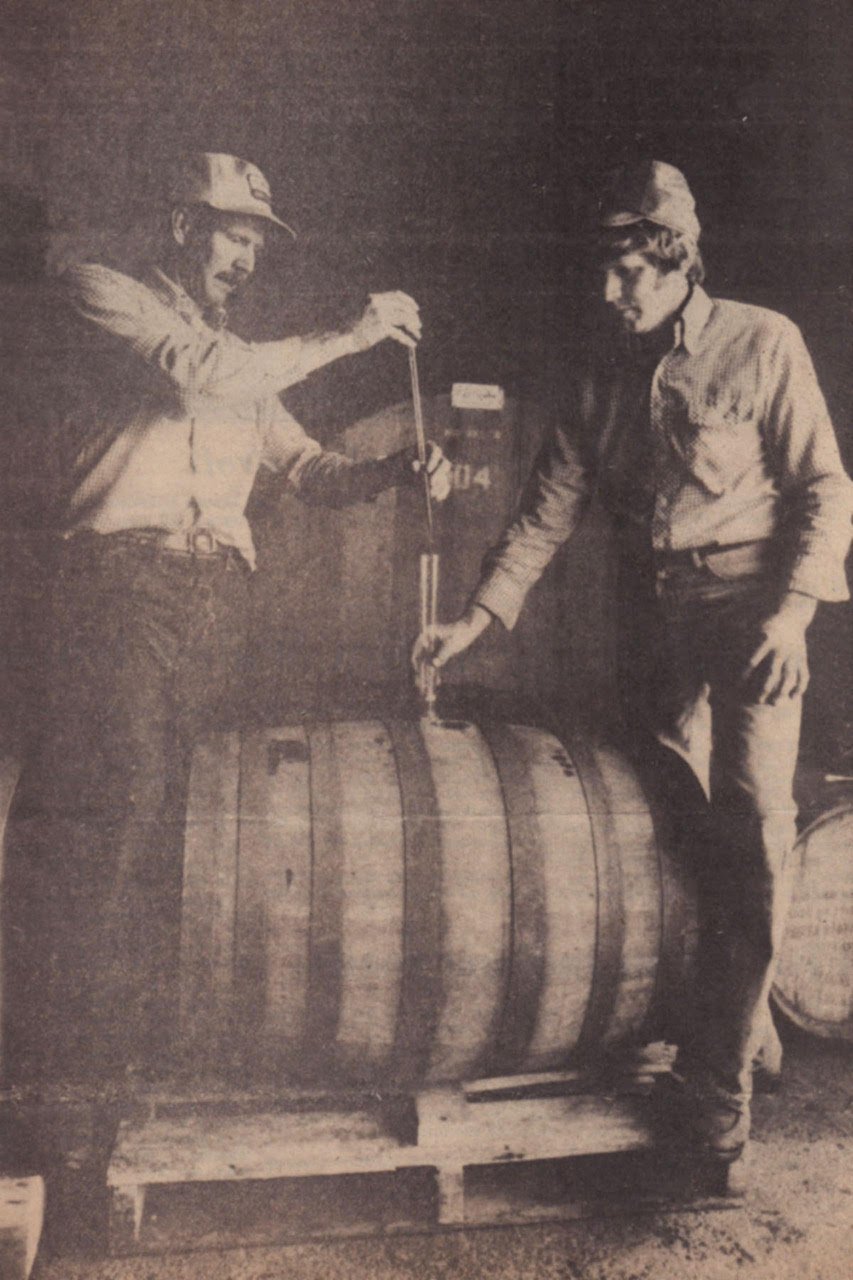

Ted was interested, and he and cousin and business partner Greg dug deep into Indiana’s legislation, hoping to make distilling legal again in the state post-Prohibition. In 2000, the laws bent far enough to allow the distillation of brandy; in 2001, Huber Orchard & Winery’s distilling business launched once more with an 80-gallon Christian Carl pot still.

“I think when Dad and Dave Pickerell got together, that’s when the mindset went to whiskey.”

The American Distilling Institute, commonly known as ADI, was Ted’s gateway into bourbon. In fact, one of the first ADImeetings was actually held at the Huber winery due to its central location. Dave Pickerell, Master Distiller described by some as the ‘Johnny Appleseed’ of craft distilling, helped guide Ted’s first steps beyond fruit brandy. “I gotta give it to him - he had so much foresight, I don’t think anybody ever saw.” Christian remarks. At first, like many whiskey entrepreneurs, Ted had planned to source product from Indiana’s heavy hitter MGP. Dave presented Ted with an alternative. “He told us, basically, at that point ‘You need to choose. There’s two paths; you’re an independent bottler or you’re a distillery.’ And that was one of the fundamental decisions I think Starlight made early on.” Christian says. Dave’s foresight saved Starlight from the problem many companies that source their whiskey face later on - the process of moving from sourced product to their own product. Although it wasn’t legal to sell yet, it was perfectly legal for Ted to play around with different mash bills, experimenting and perfecting his own bourbon.

In 2013, the law in Indiana opened distilling up a little bit further - finally, they could make bourbon for sale. In came a 500-gallon pot still from Vendome Copper & Brass Works. “I will put my life on [the fact that] they make one of the best stills in the world.” Christian asserts. Readers who are doing the math might note that Christian was not even of legal drinking age back in 2013; despite the inability to enjoy the product, he had already had his turn at the still. “It’s a Huber tradition–this is not a lie–the day you turn fifteen years old is the first day you get to distill. My dad did it on his fifteenth birthday, I did it on mine, Blake did it on his. We all made applejack.” he confesses with a smile.

Although Starlight Distillery is a family business within a larger web of separate family businesses, Christian and Blake didn’t simply grow up and get the reins handed to them. “Me and my brother were fortunate to be the first to gain Viticulture and Enology degrees from our college programs” Christian tells us. “My dad wanted me and my brother to gain experience outside of our family business before deciding our longer term career goals. When it came to the “respect aspect” of family business, he always said you’d gain more respect working outside of the [Huber] company and bringing that knowledge and skills back to the family.” he reveals. Both brothers studied and worked far away from Indiana within other spheres of the beverage alcohol industry, specifically in winemaking. Christian himself lived in southern Italy for a time working for a winery there. Eventually, however, both Huber brothers would come home of their own volition after harvest internships in Napa. “You learn quickly from these internship experiences at other wineries that you choose to work seven days a week. Every day you wake up as the sun rises because you’re picking grapes and you don’t go to bed until 11 because the still is running. Just sacrifices you make because you love what you do.” Christian explains. “I would not have come back and chosen any other lifestyle, because I do love what I do.” he says simply.

“You can’t rush time. There’s a reason why time is on your side in integration. There’s no amount of soundwaves, no amount of extrapolation that you can do to a whiskey to make it age quicker.”

Starlight Distillery made a choice at the beginning to rely on their own product, not sourced distillate. Two and a half years after the inauguration of their stillhouse, they put out a two-year whiskey. “It is a hard, hard, hard way to go about, two year whiskey. I mean, you know it’s challenging. I say that smiling because I can’t believe we got through it. Right? It was a long road between two to four year [whiskey].” Christian recounts. “Not to say it was bad, not to say it was flawed, it was just–two year whiskey.” he adds. “I taste a lot of our two year whiskey we put out, I shake my head at, going ‘I can’t believe we put a label on it.’ But, it’s a craft distillery. We were self-funded, we wanted to be able to get a product out there, we were excited, and…thank god we’re at four years.” he laughs.

Despite the challenges of raw early product–something almost all distilleries face–Starlight was a success. Part of that, Christian surmises, is getting lumped into Kentucky’s Bourbon Trail tourism by simple proximity. Downtown Louisville is just twenty minutes away, close enough for Christian and his girlfriend to go for date nights. “We’re closer to Louisville than a lot of the heritage brands that are in Bardstown..” he points out. Tourism, along with startup money from the farm and winery side of the business helped, as did their white spirits. “For us, to sell our vodka and gin in craft cocktails was a necessity for us to be able to put money back, to put barrels back.” Christian explains. Previous experience working with the TTB and understanding taxes from a winery’s point of view helped the distillery avoid pitfalls often encountered by newcomers to the industry. Ever-practical, the Hubers also recycled old winery equipment for the new distillery endeavor. Even the old 30-gallon pot stillChristian and Blake distilled on for their 15th birthdays is part of it, albeit in a symbolic capacity. It resides in the tasting room today, a somewhat anonymous-looking pile of copper that few recognize for what it is.

“Being able to work in the wine side of the community gave me and my brother such a different philosophy of distillation.”

Starlight Distillery’s approach to whiskey is, by their own admission, somewhat unorthodox. “Whenever you look at what we produce, we try to go for quality over quantity, and quantity over consistency.” Christian says. Both he and Blake did their senior dissertations on wood oak extraction, which now informs their approach to whiskey. “What me and Blake try to do is take the wine-making philosophy and really hypercritically look at oak choice, and positioning in rickhouses, and personalizing the distillate going into that oak barrel. Taking that philosophy just like we do with wine, right? You don’t put the same oak treatment [to]...a Syrah that you would to a Cabernet Sauvignon.” Christian explains. This is why Starlight uses seven different cooperages for their barrels. Always, however, 53-gallon barrels. “I can’t tell you–and any distiller that will ever read this–why 53 gallons just work. It’s something where integration just happens.” Christian says with a shrug. They employ a variety of toast and char levels, and, naturally, different varieties of oak as well.

Besides Ted, there are just four people working at Starlight Distillery (that number includes Christian and his brother). “There’s four of us, and…none of us are over thirty. If that doesn’t shock a lot of people, I don’t know what will.” Christian says with a grin. “All of us, at the end of the day, are chemistry geeks.” he declares. But it takes more than intellectual capacity to get yourselves named the Ascot Awards’ 2022 Craft Distiller of the Year. It takes a good nose, a good palate, and plenty of grit. “When we are cooking those grains, it’s just paying attention…being able to look and smell what you’re doing.” Christian tells us. “Those yeasts are stressed or happy, depending on what kind of body they’re going into.” Not only must they be able to tell whether the microorganisms bubbling away in the fermenters feel like they’re on vacation or need a vacation day, but they also need to taste, taste, and taste again. “There is no standard operating procedure when it comes to cuts; it is all based on taste.” Christian reveals.

Starlight uses skinny, closed-top fermenters, allowing them to tailor each grain’s transformation. They have three different rickhouses as well as a wine-cellar environment where they store their products, choosing the placement according to what they think each barrel will need. “We’re very lucky that we have soil and temperature probes throughout the property from the agricultural-based company, so we’re able to position our rickhouses based on the data we’ve collected over the last twenty-something years on the property.” Christian says, eyes bright with chemistry-geek glee. “We’re engineering this product from the very moment it’s being fermented to where it’s coming out as the barrel choice.” he sums up. How then, does Starlight produce a consistent product? They take the results of all these divergent distilling journeys and blend them - just like wine.

“We want everyone to know what our values are and what we stand for. We’re Indiana’s largest sustainable farm-to-bottle craft distillery, and that’s what we’re about.”

Starlight Distillery’s roots in a 7th-generation farming family are an integral component of its existence. The very intent behind starting the distillery, in fact, was to help keep farming alive and well in Starlight, Indiana. The town–these days, simply an ‘unincorporated community’--has always been known for growing corn. The Huber family grew it, as did many neighbors. Most of it has historically been sold to huge conglomerates. Starlight Distillery offers local farmers a new avenue: sell to Starlight, and you know where your crop ends up. Five years down the road, you can hold the bottle of bourbon in your hands that came from your field of Pioneer White corn. “My generation is getting out of [farming]. A lot of us didn’t want to get into it. We’re giving these farmers from the next generation kind of a different perspective on what they’re doing, right? It isn’t just growing corn, they can see the finished product and know where it’s going to.” Christian explains. They do require certain sustainability practices and non-GMO produce from their farming partners, and they happily pay extra for this. “It’s super-important as a whole to be able to support the community at large. A rising tide raises all ships.” Christian tells us. This concept is the reason behind Starlight Distillery’s name. “We wanted this distillery to represent what is best about the community, not what was best about the family.” Christian points out. To drive the point home, they named it for the community and not the Huber legacy.

Legacy, Huber and otherwise, is what drives Starlight Distillery’s commitment to sustainability. “It’s hard, because you know you can plant more. You know you can crop more. That will equal more barrels and more money, and more money is supposed to equal more security. But with agriculture, if you strip that land out and you strip everything out of your soils, there’s not much left.” he explains. “For my kids to take over the company at large, I want to give them a farm that can produce grains of quality. If I cash-crop the farm, the soils will be totally finished by the time I die. My kids would never be able to give it to their kids.” he says. Distillation, to Christian, is not a get-rich-quick scheme. Like farming, it’s a long-term prospect that–managed carefully–will give returns for generations to come. At the end of the day, he says, “You don’t become a 179 year-old company without having sustainable practices.”

With this farm-to-bottle emphasis, is Christian a distiller, or a farmer? “Yes, I do think of myself as a distiller, but a distiller is nothing without a farmer.” he answers. “If someone is trying to start a distillery, something I will tell you [matters] is selection of good grains…that’s so important.” he counsels. “We’re an agricultural-based company, and every single distillery is. They have to be.” he adds. To distill, one must understand agriculture. After all - “No distillery out there can make what they make without a farmer. Period.” he asserts. In the future, Starlight Distillery is hoping to move from simply sustainable farming to regenerative farming. “I think the distillation community, as a community, that’s so important for everyone to get used to. Especially as everyone is doubling and tripling capacity, and every single month you see this massive new distillery starting…check on the farmers.” Christian pleads. “We don’t want to ruin the American heartland with just a bunch of cash crops…We want to make sure the industry is set up to not only go through this generation, but generations past us.” he finishes.

“If a marketing agency tried to make up our brand values, then it’s already artificial from the get-go.”

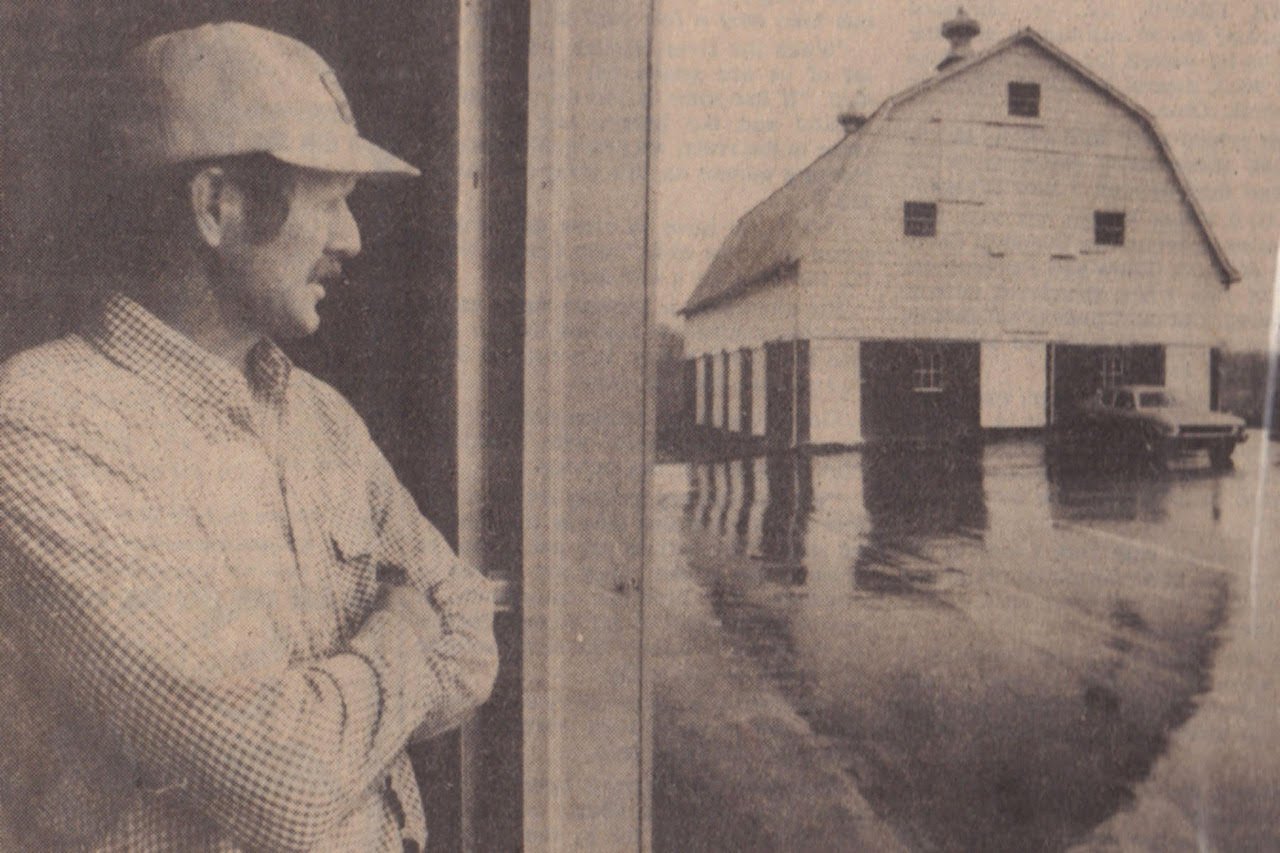

When it became clear they were going to be going from Ted’s happy 200 barrels a year to the current 2,000 barrels–each–of rye and bourbon a year, the family sat down and got to defining their values for the brand. Transparency and sustainability were among them, but so was something you rarely see in marketing a business: vulnerability. “The reason vulnerability was such a strong point for us was to say, ‘Hey, we’re not perfect.’” Christian explains. “Having a farm is the most rewarding thing you could ever do as a craft distillery…but it’s something you honestly have to give a lot of time and effort to. It’s not a secondary to the distillery, it’s a primary.” he points out. This vertically-integrated model means they’re at the mercy of Mother Nature. A freak hurricane once devastated the corn crops locally, forcing them to source their corn outside of the Starlight area for those batches of whiskey. A neighboring farmer, overzealous with his Round-Up, sprayed their non-GMO (therefore not ‘Round-Up ready’) fields, killing 20% of their corn another year by accident. Starlight Distillery is transparent when calamity strikes; instead of obfuscating the problem, they simply explain why some of the grain came from somewhere else this time.

Their bottle illustrates their evolution as a brand. From the earliest two-year batches in tall, skinny bottles to the current weighty custom glass, you can track Starlight Distillery’s learning and growth. Through it all, they’ve kept a version of their star logo - made to echo the stars painted upon Starlight, Indiana’s water towers. Today’s bottle is a beautiful custom design with a deeply practical origin. “We wanted something that was going to be strong. To be able to take a hit. We live on a farm, where pallets can sometimes fall down because of the tractor trying to back out of the bottling room–that happened last week–so we wanted a bottle that was going to be strong.” Christian explains with a rueful smile.

The bottles are rich with detail, including a recessed area for the label (visually interesting, and also presumably useful to protect the labels from scuffs and tears), reinforced top and bottom, and a simple star etched into the bottom of the glass. “We just wanted to make sure we covered all the little details.” Christian says proudly. In fact, each label even tells you who made the whiskey inside–C. Huber for Christian, B. Huber for Blake, and so on. Their reserve bottles are marked by a wax-dipped top, different colors signifying different reserves. A wax-dipped whiskey bottle is certainly evocative of Kentucky bourbon tradition, but that’s not the only reason Starlight uses it to denote their special whiskeys. Frankly, it’s less costly than other fancy embellishments to the bottle - and they pass the savings on their packaging on to their buyers. “We want to keep it at a price point that is fair. We’re farmers. Corn, rye, wheat, and barley. And yes, as a craft distillery your cost of goods is a lot more than a big distillery, I understand that. But there is something to be said for keeping prices set where it should be.” Christian explains.

“You can’t teach just sheer love for something, right? You can’t teach it, you either have it or you don’t.”

Everyone at Starlight Distillery seems to have one major thing in common: they love it. It seems almost everything has been adaptable along the way, from bottle design to cooperage to yeast strains and more. To cope with that adaptability, the culture - in other words, the love - has had to be the guiding force for the team. While knowledge and skills are obviously important, above all things their people must be a culture fit. “We surround ourselves with people of like minded-ship who want to create something that is spectacular, not mediocre. We don’t want people who just get a paycheck, we want people who are pushing innovation and pushing us to be the best ourselves.” explains Christian.

The innovation will undoubtedly continue–in fact, Starlight Distillery has an 18-inch column still on order that should arrive this year. They plan to run a hybrid process with it, giving them even more room for flexibility and experimentation. Starlight Distillery can reach higher and higher, secure in its foundation stretching back through the years to Simon Huber’s first brandies squeezed from the lowly brambles of a new land. Christian Huber is reprising his ancestor’s modus operandi; innovation and tenacity in the face of challenges. He loves what he does, and that, perhaps, is what every farming and distilling family who’s made it through multiple generations of their work has in common: they love, and they persevere. We expect to see Starlight Distillery continue to flourish under the dedication of the people who run it - and we can’t wait to see what the Huber creativity will bring next. After all, as Christian told us, “Every single day is a new day to make a great barrel, and you never know where that barrel is going to end up.”

Tasting Notes:

Carl T. Bourbon (46% ABV)

Nose: Baked Apples, Toasted Marshmallow, Toasted Almonds, Burnt Wood

Palate: The mouthfeel is light and oily with sweet notes of vanilla and caramel up front. The vanilla grows throughout, met with soft spice, orange peel and oak on the mid-palate. There is a medium, mostly sweet finish of vanilla, dark chocolate, apple and tobacco.

This is a really approachable bourbon. There is plenty of sweetness to appeal to the regular bourbon drinker, with a nice balance of spicy and bitter notes. The oily texture of the mouthfeel lends a creamy quality that compliments the sweet notes as well.

Single Barrel Bottled in Bond Bourbon (50% ABV)

Nose: Vanilla, Cinnamon, Hazelnut and Leather

Palate: The mouthfeel is buttery with caramel apple sweetness up front. Spice grows stronger in the mid-palate leading to a long finish with notes of almonds, orange citrus and burnt buttered popcorn.

This is a phenomenal bourbon. Considering the proof, it’s surprisingly soft up front. The heat comes in slowly across the palate landing nicely on the finish. It’s very well balanced with a lot of wonderful flavor.

Old Rickhouse Double Oaked Rye (53% ABV)

Nose: Cream Cheese Frosting, Vanilla Cake, Honey Coated Cashews, Tobacco and Cinnamon

Palate: The mouthfeel is sharp and spicy with vanilla and cinnamon up front with heavy spice and oak coming through on the mid-palate. Red grapes, orange peel, pepper and oak dominate on a medium finish.

This whiskey drinks much hotter than the two bourbons, and the extra oak influence brings forward a lot more spice and tannic notes. All in all, it’s still an enjoyable whiskey, but less approachable than the other two.