ADI Conference 2023 Pt. 2

By Devin Ershow

At this year’s American Distilling Institute Craft Spirit’s conference we got to sit in on several incredible presentations that covered every step of the process of whiskey production. From the kind of grain you use to the method in which you age your spirits we took away a lot of knowledge we want to share with you. This is the second part of our two part article covering the ADI Conference. This one gets a little bit nerdy, but we know a good portion of our readership are here for it!

CORN VARIETAL’S IMPACT ON FLAVOR

The concept of terroir in whiskey has been a long contested and debated topic in the industry. There are many who want to take advantage of their regional geography and local grains to try and differentiate their products from what is on the market, but there are just as many if not more that would say that the industrial act of distillation removes any impact the grain or soil have on the spirit. In recent years, much more attention has been paid to grain varietal influence on aroma and flavor. In one of our earliest features, the good folks at Far North in Hallock, Minnesota shared their Rye Varietal study which contained very convincing data to suggest that in spite of the process distillation, grain varietal does change the aroma and flavor of a raw distillate.

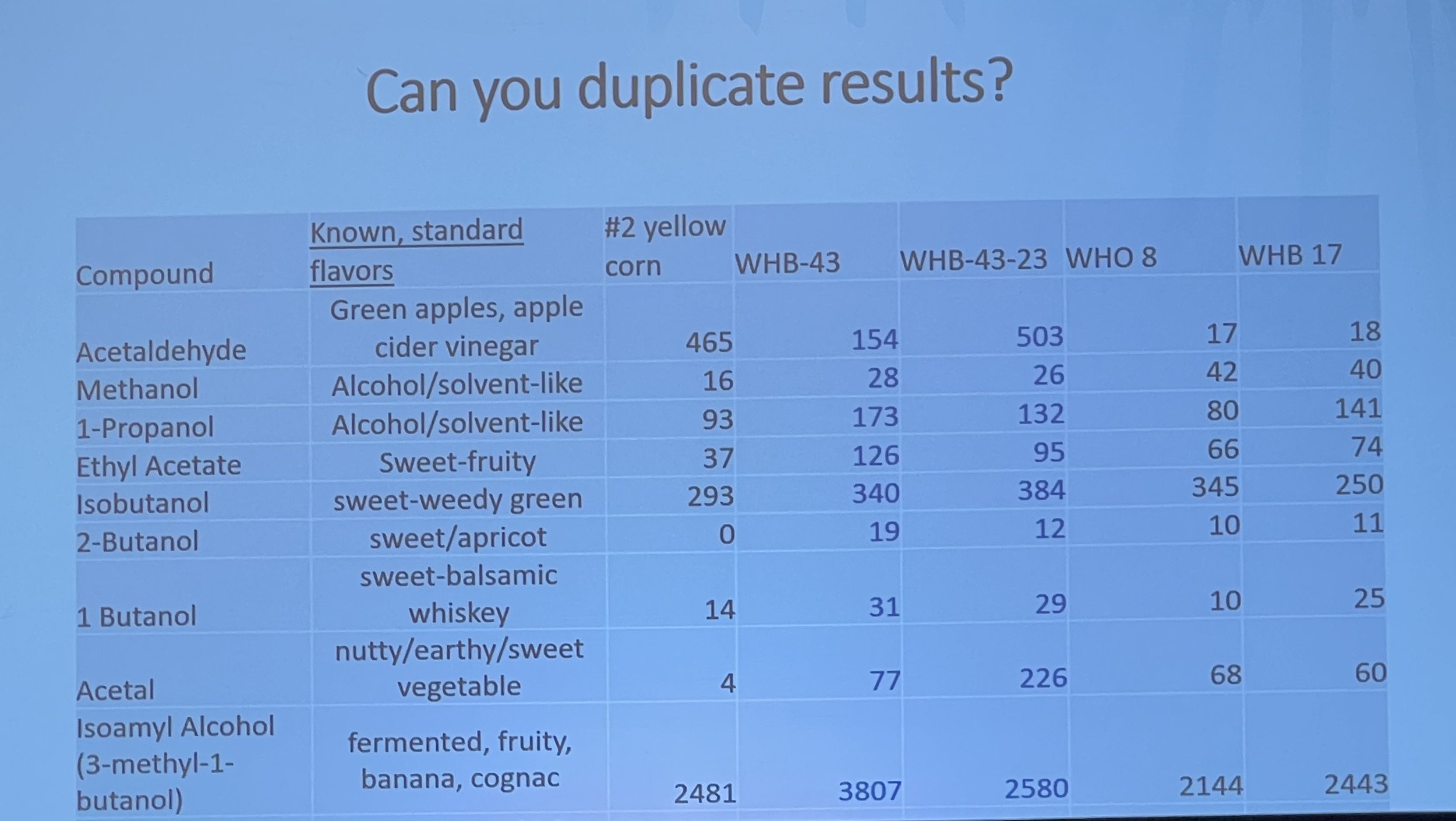

At the conference, Gary Hinegardner of Wood Hat Spirits in New Florence, Missouri gave a presentation on the developments with corn whiskey and the importance of using heritage corn over the more commonly used Yellow Dent #2 varietal. There is a reason Yellow Dent is the most commonly used strain of corn in American whiskey production. It’s all about the yield. Yellow Dent has been cultivated to be easy to grow and the starch content is maximized to yield the most potential alcohol. Unfortunately, what you gain in ABV does not correlate to what you get back in flavor, and Gary has the data to prove it.

Through his research he has overseen the growth and development of several heritage and hybrid varietals of corn and he breaks down the distillates on a chemical level. We won’t show many photos of the presentations we witnessed as we don’t want to step on the toes of those who put them together, but here is one slide that shows a comparison of the chemical makeup of Yellow Dent versus some of Gary’s heritage strains.

MARVELOUS MALTS

Malted barley is one of the most commonly used grains across the world for making whiskey. The main reason being that malted barley has a naturally occurring enzyme that converts starches into sugars. For those that don’t know, you need sugar to produce alcohol. Whiskey as an overarching spirits category needs to be produced from grains, and since grains are starches, without that starch to sugar conversion whiskey wouldn’t exist. In modern distillation you can purchase and use artificial enzymes to achieve this conversion but many distilleries still use malted barley to aid in the process. That said, for generations malted barley was not seen as something that was necessarily inherent to the final flavor of the whiskey and was merely a scientific necessity. That is starting to change as the focus on grain impact on flavor continues to increase and with the growing American Single Malt movement (more on that later in this article). Nowadays there are a lot of farmers, maltsters and distillers that are playing around with different kinds of specialty malts to create their unique products. Country Malt Group gave a fascinating presentation on the creation of specialty malts.

Let’s start with the basics of creating malted barley. In order to malt barley you take the barley grain and steep it in water. This prompts the seed to start growing and germinate. During germination, under a controlled environment, the seed begins to change. The enzymes are unbound so that the starches within the grain can be converted to sugar that the seed can feed off of in order to produce the energy it needs to become a plant. The seed is then kiln dried to halt the growing process, lock in those sugars, create flavor precursors and product stability. You now have malted barley. Complex chemical reactions, similar to a maillard reaction occur during kilning, so it is here that you can really change and define your malt. We won’t take the time to break down the process for achieving every different kind of malt, but here is a slide from their presentation that shows you some of the variety of specialty malts they produce.

The impact these malts can have on the future of craft whiskey could be immense. Distillers can get a sense of the flavor profile of these malts by using a tea steeping method or “cupping” as it’s known in the coffee world. This is where you grind and steep the malt in hot water, much like a tea and then taste the liquid results. This method can help distillers to find the right malt or blend of malts to create a product that truly stands out. Often, the incorporation of specialty malts will also require some adjustments to the mashing and fermentation approach as not all malts act the same. Some release their sugars and enzymes at different temperatures, some need to be held at certain temperatures for different times, and of course the right choice of yeast and fermentation method will need to be worked out to get the proper flavors out in the final product. The work is not for the faint of heart, but the results can be game changing. To quote a slide from their presentation, “specialty malts are a cornerstone of modern spirit production used to intrigue the senses and captivate the palate.”

Wood Seasoning Impact on Maturation

Head Distiller from Redwood Empire in Northern California, Lauren Patz gave an interesting presentation on wood seasoning and the impact it can have on whiskey maturation. To start, let's discuss the basic makeup of the most popular kind of wood used in whiskey production in America, American white oak. Also known as Quercus Alba, it is mostly composed of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, tannins, proteins, fatty acids and polysaccharides. The point of seasoning your wood is to help change the chemical composition of the wood to achieve better development of color and flavors for your whiskey. Seasoning is the process in which the wood is dried to adjust the moisture content. There are two common forms of drying, air dried and kiln dried.

Kiln drying is a more rapid form of seasoning, whereas air drying can range from 6 months to over three years in some cases. The upside to kiln drying is obviously expedience. It is less expensive and more readily available. The downside is that it does not allow for the time for the chemical compounds in the wood to break down and develop. Though air dried staves are more expensive and take longer to cultivate, here are some of the positive results that come from air drying. UV rays from the sun penetrate the wood and travel through the lignin to the cellulose and hemicellulose. This energy transfer is crucial to the breakdown of the wood sugars in the hemicellulose into simple sugars. While the ultimate goal of seasoning is to lower the moisture content in the wood, moisture is necessary to promote microbial growth that will continue to help break down these wood sugars. Lignin, famous in the whiskey world for transforming into a number of flavor compounds such as vanillin, which gives whiskey its recognizable vanilla notes, “requires fungal influence to degrade the presence of microorganisms linked to chemical transformation of wood.” Seasonal changes like temperature swings also help in the process.

During Lauren’s presentation, we got to taste three whiskey samples. Each whiskey was from the same lot, distilled on the same day in April, 2018. The mash bill was 51% corn, 41% rye, 5% wheat and 3% malted barley. They used the same cooper, Speyside Cooperage. Each barrel was toasted with a number 3 char. They were all side filled barrels and proofed down to 90 proof for bottling. The only difference between the three samples was the length of time the staves for each barrel had been air dried. The first sample was air dried for 12 months, the second for 24 months and the third for 36 months. The resulting whiskies were quite different, though the room was relatively split on which one was preferred, so we are not here to say the longer or shorter the better. What we did walk away realizing is how important this part of the process can be to your final product and the kind of questions you need to ask your cooper when selecting the barrels you are going to be using. Questions like, what kind of seasoning do you do? If air dried, how long do you or can you dry the staves? What season did the process start in? What is the location of the mill and stave yard? What is the price and of course what is the availability?

LONG TERM MATURATION

While we’re on the topic of maturation, let’s talk about something that every whiskey lover is scouring their liquor stores in search of, high age stated whiskeys. The obsession with products like Pappy Van Winkle, Weller, Elijah Craig and a number of other brands that produce whiskies with age statements reaching 18-23 years has the American whiskey world crazed for older matured whiskey.

This is a relatively recent phenomenon. Ever since the creation of the Bottled in Bond Act of 1897, and even before that, 4-year-old whiskey was considered well aged. Age statements on bottles didn’t even become prevalent until whiskey sales started to dip in the 1960’s and 70’s. In fact, the elevated age statements on the bottles were done as a marketing ploy to try and help sell whiskey that otherwise was not selling. So, while it is not true that older means better, this is something that craft producers in the modern era have had to fight against as they start up. Not only are craft producers not able to meet the day to day production output of the larger legacy brands, but they also have a harder time holding on to their older aged whiskies as demand for their products increase over the years. That said, for those that are well equipped and able to plan for the future there are a few things that craft producers can do to make sure that one day in the future they are able to put out products with some impressive age statements.

First, let’s talk about some of the challenges that long term whiskey maturation faces. Let’s start with the barrels. In America, we tend to use new barrels. This means that the barrel has never been used for anything else. We do that to extract a deeper color and richer variety of flavors from the wood, but that also means that we have more access to the bitter tannins in that wood. Additionally, the temperature and humidity play a huge role in the maturation process. As temperatures rise, the wood expands which makes it easier for the whiskey to enter the staves and dissolve the wood sugars and tannins. When temperatures drop, the wood contracts which pushes the whiskey back into the barrel. I like to think of it as the barrels breathing in and out as the seasons change. This seasonality is very important and is why most barrel warehouses will not be temperature controlled. In some parts of our country these seasonal changes can be extremely dynamic, especially compared to the likes of Ireland and Scotland. Whiskey was invented in Ireland and passed on to Scotland. The temperature there is relatively consistent throughout the year. For this reason it takes longer for those barrels to breathe in and out in a sense, which is why you see such elevated age statements on Irish and Scottish whiskey. Since the whiskey has to sit in a barrel for so much longer, they often opt to age their whiskey in used cooperage to avoid what we call, “over-oaking.” Over-oaking is when the whiskey spends so much time in a barrel that you move past any semblance of balance or complexity you were hoping to achieve and everything starts to taste like pencil shavings because the tannins have taken over.

So, given the large temperature shifts in some parts of the country and the use of new barrels, how can we expect to age a whiskey for longer periods of time without the final product becoming over-oaked? Let’s start with fermentation. Aside from grain varietal choice and the breakdown of your mash bill, fermentation is where you are going to cultivate the flavors for your whiskey. These flavors are called congeners and esters, and for a product you are hoping to mature for a long time it’s important to develop a lot of these so they can evolve and change into complex flavors to balance out the influence from the tannins. Some ways to produce more congeners is to use multiple yeast strains. Each individual yeast strain will produce a different set of congeners and esters. Longer fermentation can also help give these yeast strains the time to finish the job you want them to do. So now, you’ve produced a distillers beer jam packed with congeners. You don’t want to throw all that hard work out in the distillation process, so for longer matured products be sure to consider what kind of still you are using and take a wider hearts cut. To be clear, I’m not saying to include harmful alcohols like methanol or acetone into your hearts, but lean heavier into the tails cut. The tails cut contain the heavier alcohols and fusel oils. These will lead to off flavors in a younger spirit, but can turn into really nice flavors and aromas during longer maturation.

In terms of the wood, we can take something from the last section of this article and lean towards longer air dried staves. The longer the staves have dried the more that wood has had a chance to break down and hopefully that means that the tannins will be less strong. Consider a long toast on the barrels to create a deeper layer of caramelized wood sugars. The deeper the penetration of the toast, the longer it will take for the whiskey to get to “green wood” that could lead to over-oaking. Avoid extreme char levels, like a number 4 char. The charcoal layer is there to work as a filter for the whiskey. As the whiskey moves in and out of the staves throughout the seasons, it has to move through that charcoal layer which is working just like a Britta filter does in your home. It is removing impurities from your spirit. If you are trying to put out a whiskey more quickly, perhaps you could consider a number 4 char to create a thicker layer of charcoal that will filter your spirit more quickly in a shorter period of time, but with long term maturation that thicker charcoal layer is not important as the spirit will have plenty of time to filter through a lower charcoal layer. If possible, consider using larger cooperage. When a lot of craft producers first start making whiskey, some opt to use smaller cooperage. They do this because in small barrels there is more spirit to wood interaction which can help speed up part of the maturation process. The same can be true in reverse, with larger cooperage having less spirit to wood interaction and therefore slowing down the aging process. The industry standard barrel in America is 53-gallons, but that doesn’t mean you couldn’t go with something bigger like 59-gallons or even 79-gallons. Additionally, going into that barrel at a lower proof can help with long term maturation. According to the TTB (Tax & Trade Bureau) the arm of the government that oversees the spirits industry in America, the maximum proof that you can enter into a barrel for the standardized American whiskies is 125 proof. Many will go right up to this marker, because it helps with maximizing yield on the back end. However, different wood sugars and tannins dissolve in alcohol versus water. At 125 proof you are going to dissolve more alcohol soluble elements, including tannins. Softer and fruiter elements tend to be more water soluble, so by going into the barrel at a lower proof for long term maturation you are setting yourself up for a more balanced flavor profile.

Finally, the type of warehouse you use, wood vs. metal vs. brick can impact the way that your whiskey matures. The ventilation of that warehouse is important and barrels stored at the top of a warehouse are going to be exposed to more heat than those stored at the bottom. The humidity level inside that warehouse is going to impact your evaporation rate and whether you are losing more alcohol or water over time.

All of these factors are going to impact your whiskey. The angel's share is inevitable, but if you want there to be anything left in that barrel when you are ready to bottle you have to figure out how to control these factors, and if you’re going into the barrel at a lower entry proof, you won’t want to lose so much alcohol that you drop below the 80 proof minimum that whiskey needs to be. It’s a lot to consider, but with these things in mind we’re very excited to see some big age statements coming out of craft producers in the future.

Most consumers out there know very little about the process that goes into whiskey. Some may think it’s as easy as putting some distillate in wood and waiting as long as you can to drink it. We believe that whiskey is a magical spirit, but behind that magic is a lot of planning, research, small failures and successes and most importantly, science. Whiskey is the perfect combination of art and science and that’s where the real magic happens. We hope you enjoyed this short interlude from our regular content. We’ll be back next month with another distillery feature.