Far North Spirits

Farming is as deeply rooted in America as independence itself. For our forefathers, the ability to work the land and provide for your family and community was vital and enabled them to move west and seek out a better life. In the parts of America many of us now consider as "fly over," this tradition of farming as a means to pursue independence and provide for your family lives on. From generation to generation, traditions and skills are developed, forging a bond between one’s heritage and the land. The rise of the American Craft Whiskey movement has shed new light on the importance of sourcing ingredients from local farms to create a sense of regionality. But while those relationships are important and genuine, few distillers actually grow the grains themselves. To find one that does, you may have to make quite the journey and travel somewhere unexpected. Somewhere like Hallock, Minnesota. It’s a small town of less than 1,000 people. It is there, 6 hours northwest of Minneapolis and 25 miles from the Canadian border, that you will find the northernmost distillery in the contiguous United States, Far North Spirits. Working the land that has been in their family for generations, Mike Swanson and Cheri Reese are aspiring to bring a sense of their culture and authenticity to their spirits, establish a specific northern style of American whiskey, and show people that how something is made, and where something is made matters.

Mike Swanson grew up on his family’s 1200 acre farm just outside of Hallock, Minnesota. The farm has been in his family since 1917 when his great grandfather first started working the land. They have grown a lot of crops over the years, mostly wheat and barley with the occasional sugar beets or flax, all to be used for commodities. When Mike was a kid, his father ran the farm, just as his grandfather did before that, and his great grandfather before that. It would have seemed that Mike was destined to walk in their footsteps, but he had aspirations of becoming a doctor so he left Hallock to go to Concordia Moorhead to study medicine. After graduating, Mike, an avid skier, decided to take a short detour on his journey to medical school, moving to Colorado to be a ski bum for a few years.

In 2000, Mike was flying home for Christmas, or at least attempting to fly home for Christmas. He was supposed to be traveling on a Friday, but he missed three flights and wound up traveling on Saturday instead. On the last leg of his journey, as he walked onto the plane, he realized he recognized the blonde woman sitting in his row. It was Cheri Reese from Hallock. In a town that small, you know most everyone. They had been a couple of years apart in school, and Mike felt the nerves start to settle in. Nerves aside, they struck up a good conversation on the flight, and set up a date for Christmas Day. Mike’s parents were more than happy to push him out of the house on a holiday. Mike was 28 years old and they were beginning to worry about him. Mike borrowed his Dad’s car and the rest was history. Cheri moved to Denver to live with Mike in 2001 and the two were married in 2006.

What had begun as a short detour on the road to medical school had become a 6 years, and Mike was having second thoughts about becoming a doctor. Instead, he began working in corporate marketing. Cheri was working in PR and communications, mostly in education. They trudged along in their corporate jobs, dissatisfied with the idea of running in the rate race for the rest of their lives, and yearned for a simpler life. Mike was working on getting his MBA from St. Thomas University when he was assigned a project to come up with an idea for a new venture. His mind wandered back to his family’s farm.

“I was thinking it would be really cool if we could make a finished product out of something we grew on the farm. A vertically integrated agriculture business … All of a sudden it just popped in my head. I’ve never had an idea pop into my head fully formed before but this one was really close. I wrote it up as a farm distillery making rye, and I turned it in and thought it was fun to write but that’s going to be the end of it. But I got an email from my professor that night and she said, ‘You gotta do this. This is a great idea. This is a great time to be doing this. This really seems to fit you. Sign me up for a case of the first batch.’ And she was not one to falsely encourage MBAs. I think secretly she thought MBAs were idiots.” - Mike Swanson, Co-Founder Far North Spirits

Encouraged by his professor’s support, Mike began looking into it more seriously. He researched the idea for two years, and the more he researched the better the idea seemed. In 2012, Mike quit his job and began planning the distillery full time. Now came the hard part … learning how to distill.

Mike read everything he could find about distilling. He even joined a few online forums, which he realizes now were filled with a lot of bad information. In fact, there wasn’t much good information out there. Everyone who knew how to distill was either keeping it to themselves, teaching an apprentice or selling the information as a consultant. Mike found that the best way to learn was to drive around to other distilleries and meet the people who were making the spirits. Along his journey one name kept being brought up. Dave Pickerell. As the former master distiller for Maker’s Mark, his guidance was heavily coveted. Mike called and left messages for six months, never getting a response. He decided to take one more shot at calling him on Christmas Day, 2012, and to his surprise, Dave picked up the phone. Dave asked Mike a couple questions which boiled down to who are you and what do you want to do? Mike told Dave that they wanted to start a true farm distillery and grow the grains themselves on the family farm. They didn’t want to source any spirit with the aspiration of creating a regional expression of rye. They did not want to just mimic what was being made in the south. That was sufficient for Mr. Pickerell, who agreed to fly to St. Paul to meet with them in January, 2013.

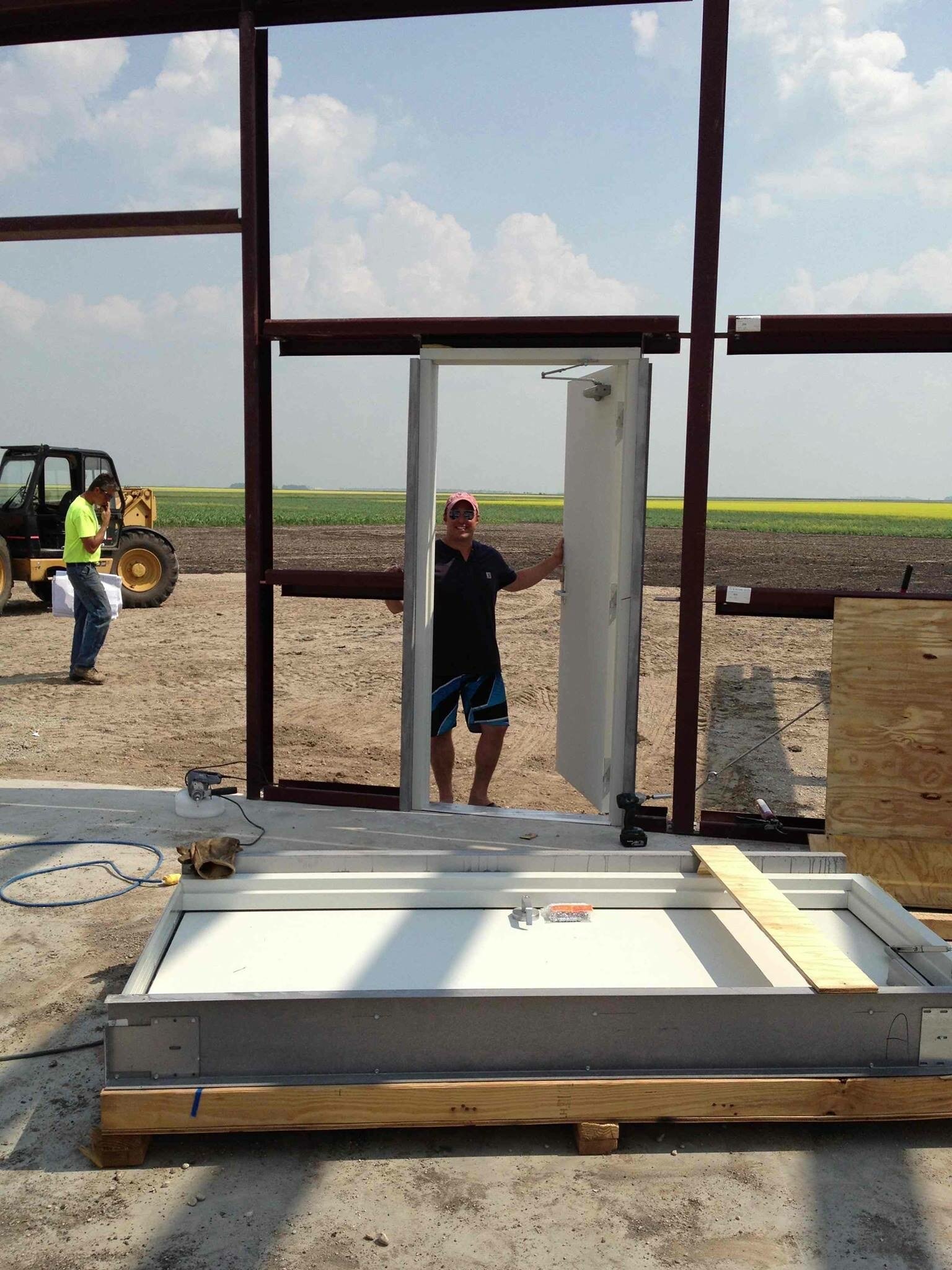

Dave helped Mike and Cheri put together the floorplan for the distillery. He saved them a bunch of money by pointing them in the right direction with equipment, and coached them through construction. Later that fall, he came up to Hallock to put together their preliminary mash bills, and to oversee the first runs off the still. Far North has a 500 gallon hybrid column/pot still from Vendome Copper & Brass Works in Louisville, Kentucky. The hybrid style allows them to make multiple spirits aside from whiskey, including rum and vodka. They do use some reflux when making their whiskey so the distillate is cleaner going into the barrel. When they first started filling barrels they could only find 10 gallon barrels due to a massive barrel shortage in the United States. Since then, they have primarily aged in 15 gallon barrels. The smaller the barrel, the less time the spirit can stay in them before the wood takes over, hence the desire for a cleaner distillate from the get go.

Before a single drop of whiskey ever flowed off the still, Mike and Cheri were focused on something that most other craft distilleries forget about until it’s already too late.

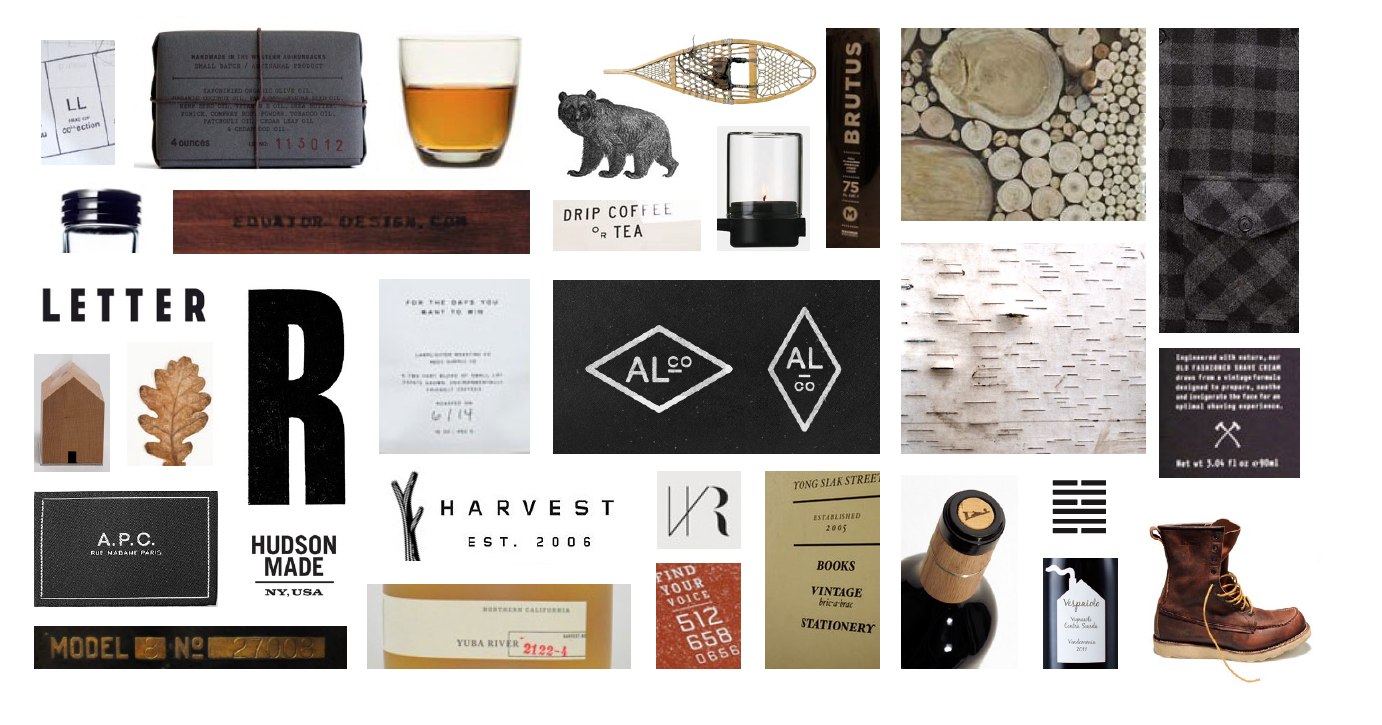

“The brand image, the brand story, the packaging, the whole works, all those touch points were of vital importance. Probably more so than what was inside the bottle, as much as a distiller hates to admit that. It is really important. We started working with a graphic designer/brand consultant before we even started talking to a builder. We were working on the brand itself before we were working on the building, doing mood boards ad nauseam just to try to flesh out what was our vision here. What does it look like and how do we represent that … We wanted to make sure that the brand fit us, because that was the entire company. It was just Cheri and I. If it didn’t fit us, it was going to be awfully difficult to represent it and sell it.”

Mike and Cheri are both of Scandinavian descent, as are most of the people in Hallock, so they wanted to find a brand that fit their style and heritage. They both like the mid century modern Scandinavian aesthetic with it’s clean lines and minimalistic approach. There is a Scandivanian concept called lagom (“la-gum”), which has been translated to “just enough,” or “sufficient.” It’s not too loud, it’s not too quiet. There are a lot of flashy labels in the spirits industry, begging the consumer to look at them. In contrast, Far North’s labels are quite simple and elegant, with just enough information displayed on the label against a solid color background. The bottle shape is smooth with gentle lines and subtle curves that cater to that mid century aesthetic. Aside from looking nice, it also speaks to who they are. Mike asserts that the concept of sufficiency is a farming mindset.

“The only thing farmers really like in excess other than yield is horsepower. Everything else is, you have just the right amount of seed, just the right amount of fertilizer, you hope you get just the right amount of rain, just the right amount of sun. There are all these things that need to be in balance for this whole endeavor to work. If things are excessive or volatile, it’s not something you look at as a plus.”

There is another Scandinavian concept called hygge (“hoo-ga”) which means the feeling of coziness or comfort. Winters in northwest Minnesota are a living force, and not for the faint of heart. If you are going to live up there, you can’t just hope to survive the winter. You have to learn to thrive in it. Aside from modern aesthetics, Mike and Cheri also wanted their brand to represent the natural beauty that their home has to offer. Their mood boards continually included winter elements, like a snowy field, a fireplace, blankets, pillows, or a leather chair. The hope being that their brand could evoke the warm and comforting pleasures of a cozy room on a cold winter’s night.

All their spirits have Scandinavian names. Their gins are Solveig and Gustaf, the rum is Ålander, the rye whiskey is Roknar and the bourbon is Bødalen. Their presentation is very similar in its simplicity, but each brand has its own personality, like individual members of the same family. Their graphic designer created icons for each spirit, a subtle expression of their individual characters. Solveig is a snowflake. Roknar is the head of a grain.

The natural beauty of Minnesota is not only present in their branding, but in the product as well. With the exception of barley, Far North grows all the grains used for their whiskey themselves. The barley is still local, sourced from Vertical Malt, a farm/malthouse run by Adam Wagner that is 70 miles south of their distillery. They have a short growing season due to the harsh climate, and their soil is slightly alkaline and jet black in color from the glacier deposits of an ancient ice age body of water called Lake Agassiz. These elements lend unique flavors to their whiskey, but they try to steer away from the word terroir, acknowledging that spirits are manipulated to a point that the word may lose its meaning. They do, however, believe in spirits having a sense of place, and that was one of the goals from the very beginning. They wanted to create a Minnesota or northern style whiskey. Aside from growing the grain a hundred feet from the still, they use open top fermenters that sit under open windows most of the year to allow for naturally occurring wild yeast to play a role in fermentation. The distillate is aged in barrels from two different Minnesota cooperages, The Barrel Mill and Black Swan, with the latter using mostly Minnesota oak. Those barrels age in a room with no insulation or climate control, allowing the temperature swings of up to 130 degrees between January and August to help the barrels breathe the spirit in and out.

In Mike’s eyes, Kentucky owned bourbon, but rye was up for grabs. They grow a varietal called AC Hazlet to make their rye whiskies. Not only is Hazlet robust enough to endure the harsh climate and keep from being blown over in strong winds, but it is also known for its big vanilla notes and subtle spices, a contrast to the peppery flavors most people associate with rye. Far North has four different rye whiskies, but only one carries the mantle of Minnesota Rye, a product they feel is representative of what northern style whiskey should be. The Minnesota Rye Whiskey is 80% Hazlet rye, 10% corn and 10% malted barley, a mash bill Dave Pickerell helped them establish. After aging in a 15 gallon barrel for just shy of two years, it is then finished in Cognac casks.

“I did a lot of talking with Dave [Pickerell] on what I wanted a Minnesota rye to taste like, and then we talked about the proportion of rye to corn to malt barley, and aging format. One of the things I thought would set it apart would be to cask finish it. I think it does some wonderful things to the finish and to the smoothness … It’s a subtle richness. The cognac cask staves are very old, so the flavors they impart are very rich but they’re not aggressive. They’re very mellow staves. There’s a subtlety to it that doesn’t have to scream at you.”

One day in 2015, Mike got a call from a farmer out in Maine who was interested in buying some AC Hazlet seed. When Mike asked him why he wanted Hazlet the farmer told him that he grew grains for a few distillers out east, but the rye he was growing was too peppery for them. He had heard that Hazlet was sweeter and softer, so he wanted to give it a try. As a farmer, Mike had always assumed that the differences between individual grain varietals, based on their development, would create differences in the flavors of the individual distillates, but this phone call encouraged him to look at it more closely. He figured that someone had already done a study on this, but after doing some digging and calling whiskey experts and grain merchants from around the country, he couldn’t find one.

Mike reached out to the Minnesota Department of Agriculture and put together a research study to test out his hypothesis. They planted 15 different varieties of rye, some new, some old, some bred for the north and others meant for drastically different soils and climates. They planted each variety in separate 1 acre test plots on the farm, and then milled, mashed, fermented and distilled them each on site in the exact same manner. Each of the 15 distillates was a 100% rye mash bill, and they used the same enzyme package for all of them to try and maintain a uniform viscosity. They used Lallemande DS distillers yeast for each fermentation. DS is a workhorse yeast that is designed not to produce specific congeners/esters that could create flavors that would throw off the study. The same person made the cuts coming off the still. You can learn a lot about a distillate using chemical analysis and gas chromatography, but Mike felt that whatever information you could glean from those tests wouldn’t amount to much if they are indecipherable to the average human nose or palate. The idea in question, after all, was whether or not the varietal of the grain has an impact on aroma or flavor, so their study was based entirely on sensory evaluation.

“I felt that if you wanted to see the data points pop, your sample size has to be bigger. This wasn’t something you could focus-group … so I put these distillates in front of as many noses and palates as I could find. Hundreds of people later, I had my data set. I put them in front of distillers. I put them in front of people at conventions. I put them in front of professors. I didn’t want to just put them in front of sommeliers, because that’s a selection that skews the data. I thought that putting them in front of a small number of very trained palates was going to introduce some bias into the data set that I didn’t want to see. I wanted to keep it really broad and relatively open.”

Everyone who evaluated the distillates did so blind, with no information about the varietal used in each sample. The distillates were also unaged, as a way to address the fear of introducing too many variables that could change the aroma or flavor that had nothing to do with the grain itself. The results of the study proved that there are indeed distinct and noticeable differences between the distillates. Some were more similar to each other, but there were radical differences between older versus newer varietals and the varietals bred for different regions. Far North was planning to publish the exact findings of the study at the beginning of 2020, but have delayed the release due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Their sights are already set on the future. Now that a baseline has been established that the varietal has an impact on aroma and flavor, the next step is to determine if there would be a quantifiable change in flavor if you planted the same varietal in different regions, something our last featured distillery, High Wire Distilling Company, is experimenting with as well.

Aging the distillates produced for this study was not part of the experiment, but once the work was completed Far North did put them in 15 gallon barrels from The Barrel Mill so they could see how they would change. The assumption was that the barrel would mask some of the variations in the raw spirit and slowly make them all taste relatively similar. The barrels were placed next to each other in the warehouse and rested for 20 months in new oak. To their surprise, the barrels did not mask the differences in the spirits. In fact, in some cases it seemed to amplify them.

“The subtle flavors became dramatically different flavors. It’s been fascinating to crack barrels open and taste a distillate that we weren’t very impressed with coming off the still and then you open the barrel and it is fabulous. We were not expecting that at all. That’s been the biggest surprise to me, what they do once you’ve aged them, because the differences get bigger and that’s been a lot of fun to find out.”

One example Mike shared with us was a varietal called Spooner. It did not grow very well on their land. It’s tall and would get easily lodged, or tipped over in strong winds. It was very sticky in the mash cooker, didn’t ferment very well and was a complete pain to transfer to the still. The distillate wasn’t pleasant either. It was thin and astringent, but after being in the barrel the whiskey came out complex and rich with a lot of depth and interesting flavor. Oklan was another varietal that was not easy to grow and didn’t taste good coming off the still, but had notes reminiscent of a highland scotch once the barrel had its way with it. Far North sells these whiskies as part of something they are calling their Seed Vault Series.

“Independent? Craft? Handmade? Field to glass? As more small brands join the herds, in this context, the meanings of these terms have basically turned to rubber…” - Amanda Schuster, The Alcohol Professor

This quote is on display on the homepage of the Far North website, and it is true that a lot of craft brands, or products that try to bill themselves as craft brands do use words like these to market themselves. At the end of the day, words are only words if you can’t back them up. Authenticity can’t be faked. It can’t be forced. It has to be true to who you are and what you want to do. Every craft distiller who pays fair prices to use locally sourced grains is making a legitimate regional product, and if you’re planting the seeds in the soil yourself, it becomes that much more special, because where things are made and how things are made matters. There are no shortcuts or workarounds, just heritage, tradition, inherited skill and harmony through balance. Craft distillers can’t compete with the big names in the south who have owned the American whiskey industry almost as long as the Swansons have owned their farm. Instead, they have to innovate, and research, and show the world a different way to think about making whiskey. Did you think it didn’t matter what kind of rye you use because they all taste the same? You were wrong, and with all the money and barrels in inventory, and generations of knowledge in Kentucky, it took a small, independent, craft distillery in Hallock, Minnesota, making handmade whiskey from field to glass to prove it. Far North is a great example of how craft whiskey is changing the idea of what American whiskey is or can be. They are doing it by defying your expectations and adding a subtle richness to the fold.

TASTING NOTES:

Roknar Minnesota Rye Whiskey Sauternes Cask Finish (47% ABV)

Nose: Pear, Butterscotch, Orange Rind, Pine Needles, Tree Sap

Palate: The mouthfeel is creamy with a touch of heat up front that is soft enough to be inviting. There is strong rye grain flavor up front with fig sweetness, cinnamon and dates blend with black pepper in the mid-palate, which rounds out into sweet vanilla with oak and lingering spices on a long finish.

This is a dynamic rye with a great presence. Well balanced with evolving flavors.

Seed Vault Series: Hazlet (47% ABV)

Nose: Green Banana, Honeydew Melon, Vanilla, Tobacco

Palate: The mouthfeel is dry and mildly hot. The flavor is grain forward up front with bready notes and subtle black pepper that remains balanced throughout. Sweeter notes of vanilla and red grapes dominate a medium finish.

There are a lot of similarities with this whiskey and the Roknar, which is not surprising since they are both made with AC Hazlet rye. The subtle spice and heavy sweetness make this a unique rye.

Seed Vault Series: Musketeer (47% ABV)

Nose: Clove, Brown Sugar, Banana Bread, Cream Cheese Frosting

Palate: The mouthfeel is creamy and slightly spicy up front. The spice gives way to sweet and buttery notes of sweet potatoes with brown sugar. That transitions to vanilla with some lingering peppery notes on a short finish.

The nose on this rye continued to open up, evolving with every whiff. The flavors on the palate are so unique, and especially welcome around the Thanksgiving holiday. It’s delightful to drink.

Seed Vault Series: Oklan (47% ABV)

Nose: Grass, Fresh Turned Dirt, Green Apples

Palate: The mouthfeel is oily with sweet notes of brown sugar, vanilla and cinnamon up front. They give way to woody notes in the middle with mild pepper that grows stronger and stronger as it leads to a spicy and slightly drying medium finish.

This rye has more of the traditional bold spicy flavors that you expect from a rye, but the sweet notes up front offer a smooth introduction to the heat.

Seed Vault Series: Bono (47% ABV)

Nose: Dried Flowers, Orange Citrus, Peanut Shells, Leather

Palate: The mouthfeel is creamy with fruity notes of grapes and plums up front. There is a smokiness in the middle, leading to cinnamon that is quickly followed by cocoa, black licorice, vanilla and caramel on a short finish with lingering flavor.

This is a really cool whiskey. The way it moves from sweet to spice back to sweet, while never being repetitive makes for a very fun journey.

Seed Vault Series: Progras (47% ABV)

Nose: Fried Dough, Vanilla Custard, Orange Rind, Candied Cherry, Toast

Palate: The mouthfeel is thin with sweet and savory notes up front like biting into a well seasoned pork chop with a honey glaze. Spice takes over with black pepper and paprika leading to an oaky short finish.

The nose and palate on this whiskey could not be more different. Nosing the whiskey was like walking into a donut shop, and tasting the whiskey was like eating a hearty dinner. It’s a contradiction that works in this case.