High Wire Distillery

American southern food is one of the most popular styles of cuisine, from biscuits and gravy to grits and barbecue. For generations it has delighted our palates, but what is often forgotten is that southern cuisine is the juxtaposition of influences from disparate cultures. European, Native American, West African and Spanish flavors all came together over time to make it what it is today. When people think about southern whiskey they automatically think of Kentucky bourbon or Tennessee whiskey, and thanks to regulation and consolidation following prohibition, it has been largely one thing for almost a hundred years. With the emergence of American craft whiskey over the last two decades, that is starting to change. High Wire Distilling Company in Charleston, South Carolina, is using their past experiences in the culinary world, their dedication to local traditions, research and experiments with terroir and the revitalization of forgotten and unique grains to show consumers that the ingredients you use to make whiskey matter. Where you grow those ingredients matter, and southern whiskey doesn’t all need to be the same.

Scott Blackwell is a serial entrepreneur. He started working in the food industry while in high school, with part time jobs at local greasy spoons. Aspiring to go to law school and possibly get into politics, he vowed to never work in the food industry again once he graduated from college. However, while still in school, he started to make desserts and sell them to local restaurants, a venture that proved to be quite successful. One night while watching the series “Growing a Business” with Paul Hawken, Scott took note of two young and funny guys who were being featured for their ice cream company, Ben & Jerry’s in Vermont. They were being creative with ingredients to produce fun and unique products, a concept that resonated with Scott. Despite being a young man from South Carolina, Scott managed to meet Ben & Jerry and become a distributor for their ice cream in the Carolinas. It was a crash course in business management, with Scott learning a lot of lessons the hard way. Struggling with cash flow, Scott was forced into a partnership of convenience with a couple of guys who had wanted to start a Ben & Jerry’s franchise. Before long, Scott felt like he was working for them, even though it was his company. He quit and the experience left a bad taste in his mouth.

While he searched for a simple job, free of responsibilities, he began doing corporate catering, providing breakfast pastries at the request of his friend, Mary who worked at National Cash Register. Scott had fallen in love with specialty coffee like Green Mountain Coffee in Vermont, so he brought that in to accompany his pastries. He soon expanded to boxed lunches, all of this out of his tiny apartment. His food grew so popular that he opened a restaurant, Immaculate Consumption in 1989. His obsession with coffee continued to grow, as did his appreciation for agriculture, terroir and the impact it had on the coffee beans, so he set up a coffee bar with a roasting company in the basement, dealing directly with farms to source the beans.

Scott trained at the Culinary Institute of America in the baking and pastry program in 1995. He eventually sold the restaurant and coffee bar to his manager, Rob Reed, holding onto the baking and coffee roasting components to start Immaculate Baking in 1998. Feeling like the bakery was a little more interesting, and lacking confidence that he was going to be able to make a big splash with coffee, he sold the coffee roasting company to Gervais Hollowell in 2001. Hollowell hired Ann Marshall to help him with the coffee business, which was still using the bakery’s loading dock and labeling equipment. This is where Scott and Ann met. They instantly hit it off, bonding over their shared love of tennis. They started dating, and Ann moved into marketing for the bakery. Immaculate Baking continued to grow bigger and bigger with the development of organic cookie dough and canned rolls, eventually becoming a supplier for chains like Trader Joe’s. In 2003, they broke the world record for largest cookie, baking a cookie 102 feet wide and over 40,000 pounds. They took on a venture capital investment in 2006 and sold the company to General Mills in 2012.

By this point Scott and Ann were married and wondering what their next endeavor would be. Scott was interested in craft beer, but there were already around 8,000 breweries in America, and that scared Ann. She had been looking at the data and suggested that they look into spirits. Millennials were trending towards wanting to know how things were made. Craft spirits were the last bastion after prohibition with wine, beer and cider having already paved the road. Scott was not convinced. Unlike beer, where it’s easy to make something better than what the legacy brands are making, the big names in whiskey make high quality products. Scott wasn’t convinced they could compete, so they traveled to Portland, Oregon to get some advice from a friend of a friend, Christian Krogstad at House Spirits Distillery.

“He said, ‘Listen to your wife. You guys need to do spirits. It’s going to be a thing.’ They were just starting to launch or really push Aviation at that point, which eventually sold to Ryan Reynolds and then sold to Diageo a couple weeks ago, so he really had good vision, and he seemed like a pretty intelligent guy. So I was like alright, we’re going to do spirits! We knew nothing about making spirits. Nor were we fit.” - Scott Blackwell, Co-Founder High Wire Distilling

A lot of craft distillers start learning how to distill on small home stills, but it is illegal to distill in America without a license, and Scott was scared they might blow themselves up. Once they got licensed they jumped right in and started off in a roughly 6,000 square foot space in Charleston, using a 2000 liter hybrid column/pot Kothe still from Germany. As many other craft distillers did at the time, they enlisted the guidance of Dave Pickerell, famed former Master Distiller of Maker’s Mark to advise them on what kind of equipment to buy, what kind of barrels to use, and to give them the rundown on how to distill.

“We have this computer programmable thing that will turn the steam off and on … Dave’s big thing was, ‘Turn that off. We’re gonna turn valves, and you’re gonna understand when you turn the valves, why that matters.’ He taught us a quarter turn on a steam valve and wait ten minutes. Don’t keep monkeying with it. Wait and see what happens. You’ll see that hydrometer bob. It’s temperature. You’re balancing your condenser and your steam, and you’re trying to find that balance. You’re also distilling for your flavor profile.”

Scott began to realize that distilling was a lot like baking. Give the same cookie recipe to ten different bakers and you will get ten different cookies. He was working the still a lot in the early years, alongside a man named Nick Dowling, a jack of all trades who had gone to culinary school and worked for José Andrés. Scott was pressured to get a column still, but he didn’t want to go that way. He cared more about character than consistency. While they do use a hybrid still, they open up the plates in the small column to avoid additional reflux. The shape of the still and the path the vapor must travel in order to get to the condenser creates enough reflux as is. Scott remembers how Dave used to make the cuts from heads to hearts and hearts to tails, dipping his finger in the distillate and knowing immediately from a quick smell or taste that it was time to make a change. Scott and Nick were not so confident, so they implemented a process in which they would collect the distillate in one gallon spit buckets and line them up from oldest to newest. They would then evaluate those individual buckets to determine where to make their cuts, a process they still use today.

While they took their lumps learning to distill, they struggled to find a name for the distillery. Many look to history for inspiration, but there is a fair amount of what Scott calls “dark history” in the south and they wanted to avoid celebrating something that should not be celebrated. They eventually settled on Colony Craft Beverage, an admittedly uninspiring name, but they figured their products would each be their own brand, so no one would care. But a few months later, inspiration hit on St. Patrick’s day. Scott and Ann are both fans of the romantic, pre-prohibition era, vaudeville, circus, magic scene. Scott was a big Houdini fan and Ann loved burlesque shows. They came up with the name High Wire, and rushed to amend the paperwork with the TTB (Alcohol & Tobacco Tax & Trade Bureau). Ann found an old poster of two people on a bicycle performing a trapeze act that she liked because the woman was in front and the man was in the back, so that became their logo.

They had their name, and after about a year they felt they finally had a firm grasp on what they were doing with the distillation. Now the question was, who were they going to be in the world of whiskey? How could they stand out?

“[Dave Pickerell] left us with some great information, but probably the best piece of information he gave us was he said, ‘You can’t out makers Maker’s Mark.’”

They couldn’t just make another wheated bourbon, or rye bourbon. That wasn’t special. Scott and Ann’s experience in the coffee roasting and baking companies had shown them that ingredients matter. They bring a culinary approach to their grain selection, using a process similar to “cupping coffee” in which they mill the grains down to a meal and add hot water. Once the grains have settled they taste the water and the porridge both while they’re still hot and again at room temperature. This allows them to get a sense of the character of the grain in its rawest form and detect any possible imperfections. They began experimenting with sorghum, a grain that originated in West Africa and has established deep southern roots. They had used it in the bakery and liked that there was a rich culture and history to it. As soon as they smelled the fermentation and tasted the first runs off the still, they knew they had something exotic. It was evident that it was different from corn or rye. A light bulb went off and lit a path for them. Wendell Berry once said, “eating is an agricultural act.” At High Wire they believe that drinking is an agricultural act too, so they began a revival of local forgotten grains.

They forged ahead with sorghum and began making a 100% abruzzi rye, which up to that point was only being used by farmers as windbreaks, cover crops or feed for livestock. It was ugly and puny with limited yields, but it produced an incredibly fruity, floral and exotic flavor. Scott and Ann were happy with the sorghum and rye, but they wanted to make a bourbon. They started off with a four grain bourbon made of white corn, red winter wheat, malted barley and carolina gold rice, but it wasn’t as interesting as they hoped. They wanted to bring something to bourbon that wasn’t already out there and they wanted something from their region that they could put their fingerprints on. They reached out to their friend, Glenn Roberts of Anson Mills, for guidance and Scott met up with Glenn and Dr. Brian Ward of the Clemson Research Center at Clemson University.

“Knowing bourbon is [usually] seventy plus percent corn, yet the flavoring grains are wheat or rye, it’s like what is the corn? It’s seventy plus percent, it’s doing something. A lot of people believe the barrel accounts for fifty percent of the flavor. I personally do not agree with that. I think that the base spirit or base grain has a heavier impact. The wood brings out those layers … but the flavor is there.”

Glenn Roberts had a table full of different heirloom corns, but the one that caught Scott’s eye was a red cob in the center of the table called Jimmy Red. Jimmy Red is a legendary corn, local to South Carolina, that used to be incredibly popular amongst bootleggers for the fantastic moonshine that it produced. In the early 2000’s the last known bootlegger to grow the corn passed away and Jimmy Red dwindled down to only two cobs. Those two cobs were given to Ted Chewning, a local farmer with a penchant for saving seeds, and he was able to preserve it. Scott didn’t need to hear any more. That was the corn he wanted to use for their bourbon, but the problem was there wasn’t enough of it in existence to make even one batch of whiskey. In order to make this dream come true, High Wire cut a big check to Clemson University to grow two and a half acres of Jimmy Red corn as part of a research grant. Already over budget and behind schedule, this was a big stretch, but one they hoped would pay off.

From day one of the mashing process they could already tell it was different from the white or yellow corns they had distilled in the past. It had more of an earthy, honey sweetness to it as opposed to the sugary sweetness of standard corn. After one day in the fermentation tank there was a three inch thick oil gap at the top of the tank and the distillery smelled of peanut butter and banana laffy taffy. When distilled, the mouthfeel was heavy with a thick viscosity. There were cherry notes on the palate, with some minerality and spice. They later found out that there are much higher levels of cinnamic acid (found in cinnamon), beta carotene, furfural, and several other compounds in Jimmy Red than traditional corns, lending a distinctive texture and flavor to the spirit. Julian Van Winkle, steward of the ever popular Pappy Van Winkle whiskey, told Scott that it was one of the best white dogs he’s ever tasted. Chefs from all around who tasted samples as it was aging were blown away. Those initial two and a half acres only yielded two barrels of bourbon, making it an incredibly expensive whiskey to produce, but year after year High Wire has increased their acreage and now grows Jimmy Red across five different farms. It is traditionally produced as a 100% corn. They have some 5 year old bottled in bond waiting in the wings as well as wheated and rye versions and some batches being finished in secondary barrels. Needless to say, the gamble seems to have paid off.

High Wire grows the same grains on five different farms and they mash, distill and barrel by farm. A lot of research has been done over the last several years to evaluate whether terroir exists in distilled spirits and High Wire certainly believes it does. They believe the varietal of grain that you use matters, but they assert that where you grow those grains matters as well.

“The stuff that was grown in the ACE basin was briny, because the river that runs in is a brackish river and all the water that’s going into the soil has salt in it. The plant picks that salt up… You’ll pick up some brininess in our whiskies sometimes, and it’s because of that soil.”

They did a study with Dr. Stephen Kresovich of Clemson University, evaluating the different levels of ash, carbohydrate, furfural, protein, etc. found in Jimmy Red corn grown in different locations around the state and presented the findings at BevCon alongside Wigle Whiskey, who had done similar research with rye. From their point of view there is no question that where the grains are grown impacts the final product. Whether that influence is something that consumers can easily pick up on or even attribute automatically to a specific place remains to be seen and may take time to prove out, but the phenotypic plasticity, or manner in which grains change or evolve based on its environment, is not in question. Grains that are left to naturally regrow in the same place year after year will start to drift due to cross pollination and evolution, slowly changing the chemical composition of the plant and therefore changing the flavor. In an effort to maintain consistency with their Jimmy Red bourbon, they traced the lineage of the grain back to its purest form in Mexico where they believe it originated before being brought north by Native Americans. They have been doing some controlled growing of the seeds down in Mexico so they can plant fresh seeds in South Carolina and avoid drastic drifting.

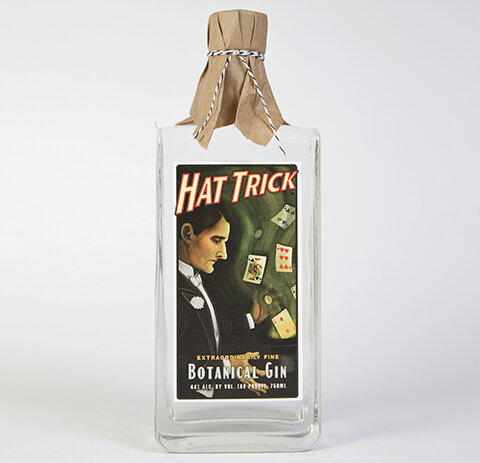

High Wire makes whiskey, gin, brandy, southern amaro, vodka and rum agricole. Each product is its own brand with its own personality. The gin evokes the mystical showmanship of that old magic era. They believe that gins in and of themselves are a sort of sleight of hand with the botanicals that are used to create the complex flavors. The brandy looks like something out of an 1800’s apothecary since they are all single sourced and done in experimental batches.

The whiskey brand is called Revival due to the fact that High Wire has dedicated themselves to reviving historical grains, telling a story about agriculture through their spirits. Ann pulled samples of pre-prohibition typography to mirror what they felt their whiskey reflected, a style reminiscent of an older time. They worked with Gil Shuler, a graphic designer, who didn’t mind Scott and Ann hovering over his shoulder to make sure everything looked exactly as they wanted it to. They chose a bottle shape that they felt expressed quality and uniqueness, something that would stand out on the shelf without having to go with a custom bottle. In South Carolina, you can’t walk out of a liquor store with a bottle unless it’s in a brown paper bag, so Ann came up with an idea to invert that concept and wrap the top of their bottles in brown paper, tied off with baking string. This is universal to all their brands, stringing them all together, and harkens back to their roots in the bakery. You can’t out makers Maker’s Mark, but you can pay homage. Makers Mark has the red wax. High Wire has the brown bag.

When High Wire opened in 2013, the country was in the midst of a massive barrel shortage. The biggest cooperages had waitlists around 18 months, so for the first 2 years they had to scramble to fill 15 and 30 gallon barrels wherever they could get them. In 2015 they moved into 53 gallon barrels from Charlois Cooperage in California and Kelvin Cooperage in Kentucky. Charlois barrels are distinctive. They air cure their barrels, which look more like burgundy barrels with long chimes. High Wire uses primarily American oak barrels with a 3.5 level char, though they are experimenting with Jimmy Red in French oak barrels as well. The distillate goes into the barrel around 105-110 proof and the whiskey ages in the same room where it is distilled. Scott believes this impacts the final product due to the steamy conditions inside the distillery, especially in the summer. The distillery is half a mile from the ocean, so they leave their roll up doors open most days to allow the salt air and humidity to aid the process as well.

The goal is to produce whiskies that are well balanced. Scott believes that too much wood is a flaw, and would prefer a balance of wood and spirit. Up until last year, when they sat down to blend they were choosing from as few as 3 barrels due lack of inventory. As a result, the blends were less dimensional, but now they are able to blend from a larger variety of barrels, anywhere from 40 to 50, often settling on 5 or 6 barrels per batch, with the sweet spot age range of 3-5 years.

In the grand scheme of things, High Wire is still a young distillery, but they are constantly pushing to improve their spirits. Unique grains and grain purity is just the first step. Scott is no longer the main man at the helm of the still. In 2017 they hired Chris Jude to be their head distiller. At the beginning of 2020 they moved into a much larger, 23,000 square foot facility. They upgraded their mill which has improved their mashes. They installed new stainless steel glycol fermentation tanks, which they keep at a low temperature for a longer period of time to develop more flavor. They have a brand new beautiful 8,000 liter Carl still from Germany that is going to be dedicated to making whiskey. It’s similar to their old still, with a few more bells and whistles, most importantly the ability to control and maintain the temperature of the water in their pre-condenser and condenser, something they battled with on their old still, especially in the summers, leading to what Scott refers to as a wilder flavor.

In addition to scaling up and improving their production, the hope was to create around 45 new jobs at the distillery to allow Scott and Ann to wear a few less hats at the distillery. Unfortunately, the Covid-19 pandemic has forced them to adjust their plans.

“Ann and I were so excited to move but also nervous about taking that next big leap only to be met with an even more giant cliff. It's been a real challenge and definitely a huge speed bump in growth, so yes it has slowed and delayed our hiring plan. With that said, we decided to take a step back and focus on the big picture. We’re laying down whiskey, focusing on seed security, re-doing the website, packaging and marketing materials while we ride out the storm. We don't have a crystal ball but we think this probably has set us back two years on the timeline with jobs, but thankfully the whiskey will continue to age!”

Scott Blackwell and Ann Marshall entered the spirits industry as two accomplished business people with a great sense of the importance of high quality ingredients as it related to food, and no sense at all on how to make craft spirits. In the very beginning, Scott was having night sweats worrying about how they were going to compete with the big names in whiskey. The truth is that craft whiskey can’t compete with the big legacy brands, or rather, can’t beat them at their game. You can’t out makers Maker’s Mark. We’re a long way off from craft distilleries rivaling the barrel inventory or generational knowledge of Jim Beam or Heaven Hill. In the meantime, what craft producers can do is dig deep into their roots to find out what makes them different and what makes them special. They can make something based on their own flavor profile, rather than be swayed by what someone else likes. They can partner with farmers, cooperages, and other small businesses to create expressions that are unique. They can invest and participate in research studies, and experiment with and revive lost and forgotten grains. They can push the boundaries of terroir and lean into regionality. They can be like High Wire Distilling Company, and strive every day to make their spirits better and make something as sacred as southern whiskey as diverse as the cultures that created southern cuisine.

TASTING NOTES:

Jimmy Red Bourbon White Dog (55% ABV)

Nose: Corn, Dried Apricot, Wet Hay

Palate: The mouthfeel is sharp and a bit oily with citrus peel up front. There is cinnamon and black pepper on the mid palate leading to earthier flavors of charred bell peppers and tobacco with a touch of dark chocolate on a short finish.

This is a really vibrant white dog. The corn flavor is strong, as is the case with most unaged corn whiskies, but there is a depth of character both in the mouthfeel and flavors that differentiates it.

Jimmy Red Bourbon: Batch 17 (47.5% ABV)

Nose: Orange Cream Soda, Strawberry, Cinnamon, Leather

Palate: The mouthfeel is soft and dry. The flavor is grain forward with subtle notes of citrus up front, transitioning to cinnamon and black pepper in the mid palate with a short smoky and woody finish.

This is a decent bourbon that shows a lot of promise. It will be interesting to see how it evolves as the whiskey ages for longer in larger barrels and the blends become more complex.

Jimmy Red Bourbon: Barrel #401: Livingston Farms, Green Pond South Carolina (55.1% ABV)

Nose: Kettle Corn Popcorn, Brown Sugar, Plum, Gala Apples, Tree Moss

Palate: The mouthfeel is thick and spicy with some saltiness up front, dissolving into caramel and pepper in the mid palate, with a long rich chocolate brownie and coffee finish.

This is a really dynamic bourbon with wonderful texture and complex flavors that are constantly changing as it washes over the tongue. The saltiness or brininess on the front palate was evident before we knew this barrel was from the ACE Basin. It lends a unique experience to the bourbon and is very intriguing for the argument for terroir in spirits.

Abruzzi Rye: Batch 17 (47.5% ABV)

Nose: Lemon, Honey, Green Apple Jolly Rancher, Sour Cherry

Palate: The mouthfeel is delicate with light pepper, orange peel and toasted bread up front. The mid palate has the brightness of lemon without the sharpness. It’s rounded out with honey like a cough drop settling on a short finish with subtle notes of oak and tea leaves.

This is a very nice rye. Beautiful on the nose and the palate. A real easy sipper and a treat to drink.